Sideways Thinking and Stranger Worlds: The Question Concerning Cyborg Virtuosity.

“I believe they are ripping out their computers and installing human beings!”

A surprise, spontaneous invitation to a meet up and Substack worlds did collide in a northern English pub. Observant readers will have noticed (“Stay wonderful!”) Chris Bateman’s frequent comments on my essays, which are always welcome. Chris is the author of Stranger Worlds a thoughtful Substack worth checking out.

So, after what must be three years, we finally met. In that strange way that often happens, one feels as though one knows a person, even when that cannot be the case. You can never ‘know’ someone without being in his presence. However, it is a good sign if one slips into friendly and unselfconscious conversation within moments of meeting. We had to date, only corresponded at a distance in that curious slow dance kind of way, a kind of (forgive me) coitus interruptus. Therefore, full belt, the unmediated and heady experience of reality reminds me that distance and mediation are amongst my most serious occupations in thought these days. A sunny day, still August, the brightness, the laughter, chatter, argument, the giving way, the stepping in. The wrestling with life’s biggest questions and concerns, the nature of existence, the contrasts in approach, the reflection of different reading and the bonhomie over a shared meal.

It seems that it may have begun with my essay Rosemary’s Baby, (still one of my favourites) a reflection of today’s world, startlingly present in a 1960s film. Shared by the fascinating Thorsteinn Siglaugsson it found its way to Stranger Worlds’ Chris, an ex pat Brit abroad. And yet I suspect it is the Heideggerian hinterland of my thought that has trodden its ‘tread-ition,’ to form a pathway connecting myself and Dr B.

The Question Concerning Technology quietly and insistently beats its little drum. Our conversation fluctuated around putting the world to rights, the wider Judeo-Christian tradition, the disagreements over the phrase itself, and yet the essential qualities of that phrase that I will need to put into words; worlds even. That one to be continued. But not now.

Chris inscribed a copy of his book for me, The Virtuous Cyborg* – which I took to be an oxymoronic, if intriguing title. The question he poses: are we already cyborgs given the interweaving we do with technology on a daily basis? And if we are already cyborgs, how do we know whether or not we are good cyborgs? I think because we are now situated within technology, rather in the way that we are situated within language, we are now embedded within a network of meanings that have arisen from this. And this is something we have not really come to terms with. Language is the house in which man dwells according to Heidegger. Added to that, the ever-present Question Concerning Technology informs this intriguing and thought-provoking work.

More drinks, and after a meal and a couple of whiskies, I get back to my room.

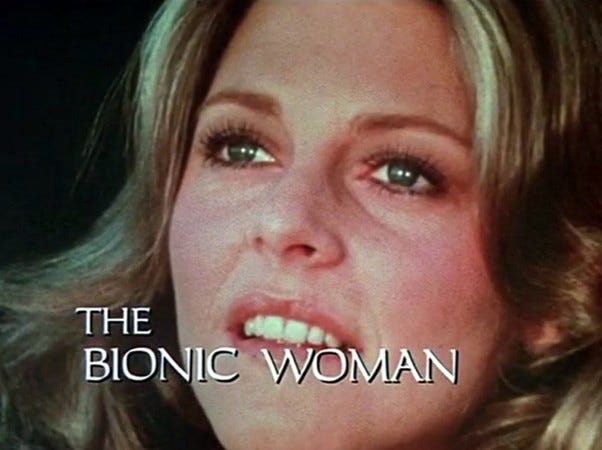

It is not too late. I switch on the television, select Prime, and opt for a childhood favourite. Of all the things to choose. Supposedly inspired by the novel Cyborg by Martin Caidin (inspiration behind the Six Million Dollar Man) – the Bionic Woman – the classic 1970s version came to life with that familiar 1970s bionic metallic juddering sound. I think about the intersections flowing from earlier in the evening. My memories and the new associations I now make with this Jaime Sommers, a ‘cyborg’ who leaps two storeys high, who can switch on bionic hearing, who can strong arm anyone, and who has such a wholesome all-American appearance. The Bionic Woman always seemed to me to epitomise something like a ‘virtuous cyborg.’ Gleaning some key points from Dr B’s book, I think about her courage, honesty, tact and insight.

Additionally, I think about that name, Jaime. I wonder how many people have considered the spelling, comprising as it does, of the French ‘I love,’ j’aime. I watch as Jaime, I love, pretends to be a nun. In one scene, there are more striking coincidences. I notice in the scene, there is a statue of Our Lady, and it bears a striking resemblance to the figure depicted in Eugene de Leastar’s painting, the Fall of Rome. I got to see the actual statue located in Ireland’s County Tipperary (and yes, it is a long way) after having reviewed the painting, a work of art and satire for (now defunct) Church Militant in the United States.

In the same nun episode, there is a wall behind the altar, and I am sure I can spot a reproduction of the William Holman Hunt picture, Light of the World hanging there. Of all ironies, Hunt had been attempting to devise a protestant visual language that reworked Catholic emblems. This painting was roundly criticised by Victorian intellectual Thomas Carlyle, as overly papist, idealised and sentimental. As a result, Hunt was moved to paint the picture I was to research for my doctoral thesis, The Finding of the Saviour in the Temple (1854-60).

These various musings point to the stranger worlds and networks of coincidences. I further ponder the astrophysics disciplinary area that Dr B started out with, and drift into thinking about the story, the Man who Fell to Earth; Walter Tevis the author and Nicholas Roeg, film director, with David Bowie in the lead role as Thomas Newton. A spaced-out man, a space oddity even, in stranger worlds than this. I often recall one scene in that film with character Dr Bryce (Rip Torn) expressing exasperation at his college Principal’s systematisation and rationalisation of everything. Speaking about World Enterprises, Newton’s company, he says: “I believe they are ripping out their computers and installing human beings; back to man and his imagination!” This was the mid-seventies. Before the total whacked out left-brainiac crunch to come. We knew all this was coming. And still it came, and still it comes.

I flip back. Jaime, ‘I love,’ of course saves the day, rescuing the convent and the nuns. She even has time to teach the nuns a thing or two about modern liberal values. She is rather like a kind of virtuous secular messianic cyborg, the fusion of human and machine installed with a kind of wholesome values software, the goodly transhuman. I have noticed that in many Bionic Woman episodes Jaime frequently gives little homilies to other characters in the show, little twee performances of virtue and kindness. Here, her transhumanist condition is presented as good, natural and indistinguishable from the everydayness of fleshy human bodies. (Why! You would hardly ever guess a cyborg was in your midst!). She delivers her sermon tactfully, because Jaime, I love, is kind and just.

Of course, as a child, this was not how I understood Lyndsay Wagner’s portrayal of the Bionic Woman. The thought of bionic limbs offering superpowers over and above what is normal and natural for a woman never fazed my younger self. I will confess that I really wanted these things for myself. I used to run round as if I were Jaime. I used to pretend I was strong to be like Jaime. All my friends loved Jaime. We discussed her clothes and her powers, and her (Wagner’s) hair…. that centre parting, the waves, or the straight style. Such an innocent girl crush. I note the title sequence’s use of the phrase Neuro-link and wonder if Elon Musk was ever a fan of ‘I love,’ Jaime Sommers.

Wagner’s portrayal of Jaime Sommers was, with hindsight, so conspicuously performatively natural. No hard body gymnastics, no snarling girl power rhetoric. It is, however, notable that the All-American bionic woman with wholesome appearance nevertheless is devoid of a life partner and rarely has a romantic interest, notwithstanding the compliments about her attractiveness that are paid to her in almost every episode. The back story is that her parents are dead and there appears to be no other family. She is then, the perfect secret agent. Alone and ever ready to serve the government in the form of the fictional OSI, (Office of Scientific Intelligence), led by the fatherly, Oscar Goldman – who frequently calls her ‘babe.’

There is an episode where Jaime has had to deal with an identical criminal lookalike who threatens her life. Despite the terrible crimes that have been committed, and moreover, against her, Jaime recognises the vulnerability of the criminal and offers words of kindness, a sort of homiletic ‘twins speak’ of the kind of advice she loves to proffer so much. Here she tells this lookalike criminal Lisa Galloway to avoid running away from herself and face up to being punished for misdemeanours. The criminal accepts this with good grace, and all is well.

In the OSI world of criminals as well as the 1970s police procedural in general, the baddies get collared in the end and good always wins out. In the all-knowing cynical world of today, this can seem incredulously naïve. But for my generation, it is now a relief to switch on my willing sense of disbelief in order to see a world portrayed in this way. It is not always about the realism after all, it is about the story, and the question of what kind of world we want. I want a story where the baddies get collared at the end and order from chaos is restored. I want the goodies to thrive. I want goodness back.

Dr B also wants the goodly world of virtue and kindness. I am reading his book. He cites a tale about Machine Worries that speaks volumes. A traveller offers a farmer a machine that will be a more efficient means to water his crops. The farmer replies:

Where there are machines there will also be machine worries, and where there are machine worries, there are machine minds. When you have a machine mind, you’ve spoiled the simplicity of it all, and without simplicity, the life of the spirit knows no rest. It’s not that I haven’t heard of your machine – I would be ashamed to use it! (Bateman, 2018, 35)

Drawing upon Martin Heidegger, Bateman continues to explain that to find the story absurd is to have fallen into a technological mindset, one that changes our relationship with the world, and thus being itself. To ponder a river such as the Mersey (or Heidegger’s example of the Rhine) is no longer an authentic encounter. It is now transformed via technological thinking into a resource for man’s use. This is especially (and ironically) more the case now that we are supposedly so ‘environmentally aware.’ When man thinks in technological terms, it is wind power or wave power to be harnessed that is the thing that one sees. The profit and virtue also to be harnessed is wrapped up in all of this as the current British energy secretary fantasises. One no longer sees the thing itself. One sees the use one has for the thing. One sees things in utilitarian terms, the instrumentalising of everything. There is, one might say, a great missing of the point. The question of flattening everything downwards into resources now includes human beings. We no longer have personnel departments. Everywhere these days, there is the curse of Human Resources, a kind of ‘HR Puff’ n Stuff’ for modern times.

And so it is with the question of what a woman, let alone a bionic woman, is. A collection of parts, bumps, skin, hair and holes. A person, a trans – trans-formed person, a bodily fleshy yet bionic Jaime, I love, Sommers, a Kraftwerk woman-machine.

At some point, Jaime, the woman I so wanted to be, morphed into some other woman, one I could never have been, and probably should never have seen. From wholesome natural clear skinned blonde to punk and dirty Harry Blondie. Adolescence kicked in and sexuality bubbled up. Down came the Bionic Woman posters and in came the peroxide blondie bleach. I reflect on this as I write because only now does it become unconcealed; the nature of the female heroine of my perceptions emerging from memory. And yet, there are echoes. A new collection of parts to decipher. Artificial hair, a thick made-up mask fronting a lip-synching doll mediated via screen technology. A former drug addict and Warhol darling at Max’s Kansas City. A screenprint pop of endless machine reproduction.

If I could speak to my younger self, what advice would I give… How strong would my words be by comparison with the benign neglect of my parents’ generation who stood and watched and said nothing. She’s just a new version (or iteration) of what went before. Or perhaps an iteration of Marilyn. Or not. I now would guess that her; that is Blondie’s, girl crush would have been Nico. And who would Nico have modelled? And then who else? How far does it go back? The heroes and heroines of our younger selves have an impact for sure. However, speaking of iterations, let’s switch gear a moment.

Stranger worlds collide again as my next viewing choice that evening was the film Heretic with Hugh Grant as a rather devilish figure entrapping two Mormon missionaries. He’s British, so right away we know he is a ‘baddy.’ The premise is so interesting as the Devil really does know his theology. In the film, there is the overriding emphasis upon literal, empirical truth. Mr Reed speaks of iterations and shows the missionaries how nothing is truly original; things always emerge out of what is already in existence.

The heart of Mr Reed’s (Hugh Grant) amusingly put speech is the very concept of truth. Mr Reed speaks about how things we think are unique and special, real and true are but mere iterations of previous things – and more often than not, these iterations are weaker and poorer than what went before. Not only that, but he implies that cheating happens as the newer iterations overcome the older ones. He begins with some fun popular cultural examples and then pivots towards religion. And this is where it does get interesting.

The whole premise is one of attempting to rake back to find the truth, in the fashion of an archaeological dig. He presents his thesis that there is nothing new under the sun and does so without the wisdom of Kohelet (Ecclesiastes) to boot. In a sense, his utterings are themselves poorer iterations of Ecclesiastes. I stop to think for a moment and wonder if others have spotted this. The big idea is that all we have ever done is copy what went before; and when we do so, it is not as good as the original. However, we can never dig enough to find the original as such.

After taking his visitors and the film’s audience on a journey into the labyrinth, we learn that in Mr Reed’s world, the truth is revealed to be a very dark and mean thing. And for the sake of potential spoilers, I shall leave that point resting. What should happen of course, is that the good guys win and the bad guy loses. In my leap from the goodness of Jaime (I love) Sommers who must always win out at the end of each episode, I sense that here, in Heretic world, good is not going to win out.

The assumption that surrounds both the Heretic film and the Bionic Woman is that we have always thought in this ‘raking back’ way – that is to say, to put our focus on what can be known materially, tangibly, with no imaginative or mysterious elements. If we just keep digging, we will find the original, the answer, some truth that was hidden all along. However, the more we dig, the less we find. What is more, our hubris in seeking to answer all questions, to settle all knowledge, has led us to the point of human irrelevance. Machines now sit in our places. (The clamour for driverless trains since the recent London tube strikes is a case in point).

What happens when we have objectified and quantified, flattened everything down to what is material, tangible and utilitarian? My guess is that we will lose all meaning. We will no longer see the person. We will stop seeing human beings and reduce our fellows into mere human resources and then, inevitably, we will see too many of them. Gradually, we will become useless eaters that must be dealt with. Well, what do you think the AI obsessed rulers are going to do once that point is reached on the eternal dig?

In my film studies days, we learned about the concept of unpleasure as one that emerges when we can enjoy something unpleasant happening in a film. I speculate that in a world where every type of story has been told already creators reach for twists, shocks and the unexpected. In other words, the search for more novelty leads us to misery, which as we know, likes company.

We have told ourselves that nothing is really true, there is nothing we can really believe, and that no one can prove anything. And so we have reached the point of nihilism. I know that when I watch the naivety of Jaime, I love, Sommers I choose to enter into a mode of willing disbelief. My adult self knows that Dr Rudy Wells is not a real person let alone a real scientist. I know his inventions as portrayed would not be possible. And yet, the force of collective human imagination – let us say, of writer Martin Caidin, a television company, screenwriters, actors, viewers and broadcasters, may well have prompted the world of science and maybe even Elon Musk to achieve something truly fantastic with a phenomenon he called Neura-link. This imaginative empathic conglomerate has in all probability brought movement and agility back for real people who can now use their own brains to move bionic arms and hands. Is this one of Mr Reed’s ‘iterations?’ Is it an example of a virtuous cyborgian network?

The point of my enjoyment of the Bionic Woman is not the realism. It is about the story, the narrative and who rightfully gets to win. In our world of increasing literalism and yearning for something that is ‘true’ we have lost our imaginative way. The cleverness and knowing sense of the new storytelling might not always be honest. I do not believe that we get nearer the truth the more we dig, nor the more we build our Towers of Babel.

In terms of my childhood heroines. Where Blondie was mere fantasy, one of many iterations that brought glamour and an illusory idea of sex into a TV screens. Jaime Sommers was, one might say by contrast, the product of imagination. The world of what could happen if. Imagining her bionics and the possibilities may well have led to some real and good inventions. As an iteration of an angelic saviour figure, she gets to portray something apparently, well, virtuous. We should recall that within the diegesis, she hid her special powers and used them for good. She had sacrificed her natural body parts and undergone pain to become a cyborg. Empathy and womanly characteristics were always foregrounded.

Is it better to have dispensed with the happy ending? Or was it always true that media representations create the world in which we live. Are my longings for happy endings a childish comfort blanket, or a vision of goodness I hope will spread its wings outwards? Is it better to get closer to the truth of how things really are? Or have we completely missed the point of storytelling in a good society? Could there ever be a worthwhile message in the nihilistic new storytelling? I have come to think not.

In a knowing nod to the film 2001: A Space Odyssey, Jaime I love has her own Hal moment. She must stop the ALEX7000 supercomputer before it detonates a ‘doomsday device.’ The device is invented supposedly to blackmail the world into lasting peace. It is admittedly an odd premise for it would seem to be a determined attempt to flatten the world into one Babelesque way of thinking. However, it is the phrase that ALEX7000 repeats in a Hal style that unnerves. As she, Jaime – herself part machine - tries to outwit the machine, it announces as if on a loop,

“I am programmed to win – my purpose is to win against any intruder.”

The cyborg is only ever as virtuous as the virtues that are programmed into it. And this must be the case for human cyborgs. Luckily, virtuous cyborg Jaime, I love, wins out and saves the day. She manages to defeat the menacing machine and restore a genuine peace of sorts, one that is free of blackmail and force, one with all of its messy human idiosyncrasies.

I realise that the invention of Jaime, I love, Sommers belongs in the imaginative world. She is one that is empathic, working for justice, with tenacity, speaks with tact, acts with honesty and fidelity and with a fair degree of insight. I would say that there is a chance, just a chance that with love, we can make for our selves a model virtuous cyborg. And only by envisaging a happy ending are we more likely to get one.

*Dr Chris Bateman is an outsider philosopher, game designer, and author. His book, the Virtuous Cyborg can be found and purchased here.

Thank you for reading. Please feel free to comment and share. If you find my writing interesting and worthwhile, I would be glad to receive one-off donations through the Buy me a Coffee scheme. Do subscribe if you haven’t already, subscribing alone supports my work.

Dear Caroline,

Many thanks for writing this thoughtful reflection. I think for me, The Virtuous Cyborg doesn't ask *if* we are already cyborgs, it supposes that we *must* already be cyborgs, and have been for some time - so long, in fact, that we have been so for longer than we had the word. This was one of the aspects of the Toaist story that you shared here - when even an irrigation tool brings about 'machine worries', it becomes difficult to say when exactly we weren't embedded in technology. But then, of course, there is Heidegger's warning - and this is most certainly a break in the way we think about our relationship with the world. But we were cyborgs even before everything became a 'standing reserve'....

There are two weaknesses to The Virtuous Cyborg to my mind. The first is that the concept of cybervirtue I developed turns out to be too abstract for anyone to work with. Since this is the engine of the book, I am forced to admit that it 'doesn't work', at least not in this aspect. The second is that I still supposed that our democratic institutions were functioning, just merely rusty and creaking. After 2020, it is difficult to hold faith in this, which makes the book's call for further conversations fall short. And yet, I do not know how I could update it, and when the publisher offered to do so (admittedly, at my expense!) I could not begin to work out how to reposition it after the events of the Nonsense. The space for this conversation has already closed.

Regarding 'bionic people', I was always struck that the original show was called "The Six Million Dollar Man". While certainly the wishing for bionic superpowers was intimately tied up in the power fantasies these two shows evoked, there is something about the admission that the route to such powers was through military funding that also seems to me in retrospect to be remarkably prescient. In the year's since, the phantasies have drifted into 'bionics for all!' (i.e. transhumanism), which is a patently undesirable fate. So why does anyone dream of it...?

There is a disconnect between what the sci-fi writers imagine and the role for funding in high technology, which doesn't even have to succeed in what is promised to cause great trouble. Indeed, 'pandemic preparedness' is precisely an example of rampant funding causing greater failure - 'machine worries' indeed!

With unlimited love,

Chris.

Yes I loved Jaime too, love is the answer, now what is the question. ?