David Lynch and Twin Peaks: The Truth is 'In Here,' Rather Than 'Out There.'

Upon learning of David Lynch's death, I reflect upon my own immersion into his world of Twin Peaks, Where the Truth is 'In Here,' Rather Than 'Out There.'

The man who would fish for ideas has finally gone fishing in that big river in the sky. The death of folksy voiced film director David Lynch brings to a close an era of surreal film making and artistic endeavours of many kinds. It is especially poignant for me given I spent some years studying Lynch’s work closely, culminating in a master’s thesis on his 1990s television and film project Twin Peaks. I was fascinated by his work; the way lightness and darkness were so easily juxtaposed, the way he used sound to astonishing effect and how he managed to reach a dream like state in a way that his audience could grasp with an unheimlich recognition. He was, it is said, able to reach the skull beneath the skin, with Freudian motifs and frequent nods to Alfred Hitchcock.

Lynch’s oeuvre is almost a genre in its own right which has a beautiful irony about it given the way generic forms are bent and twisted so much in Lynch’s work.

Reading one obituary, the ‘below the line’ comments reveal frequent expressions of surprise at finding out that in addition to Twin Peaks, Lynch had directed the Elephant Man (1980) (starring John Hurt, Anne Bancroft and Anthony Hopkins) as well as Dune (1984) and Blue Velvet (1986) the unofficial precursor to Twin Peaks featuring Kyle MacLachlan. Eraserhead (1977) was his first serious feature film that took him over five years to make, and remains for many, a confusing and fascinating take by an American on European Expressionist film.

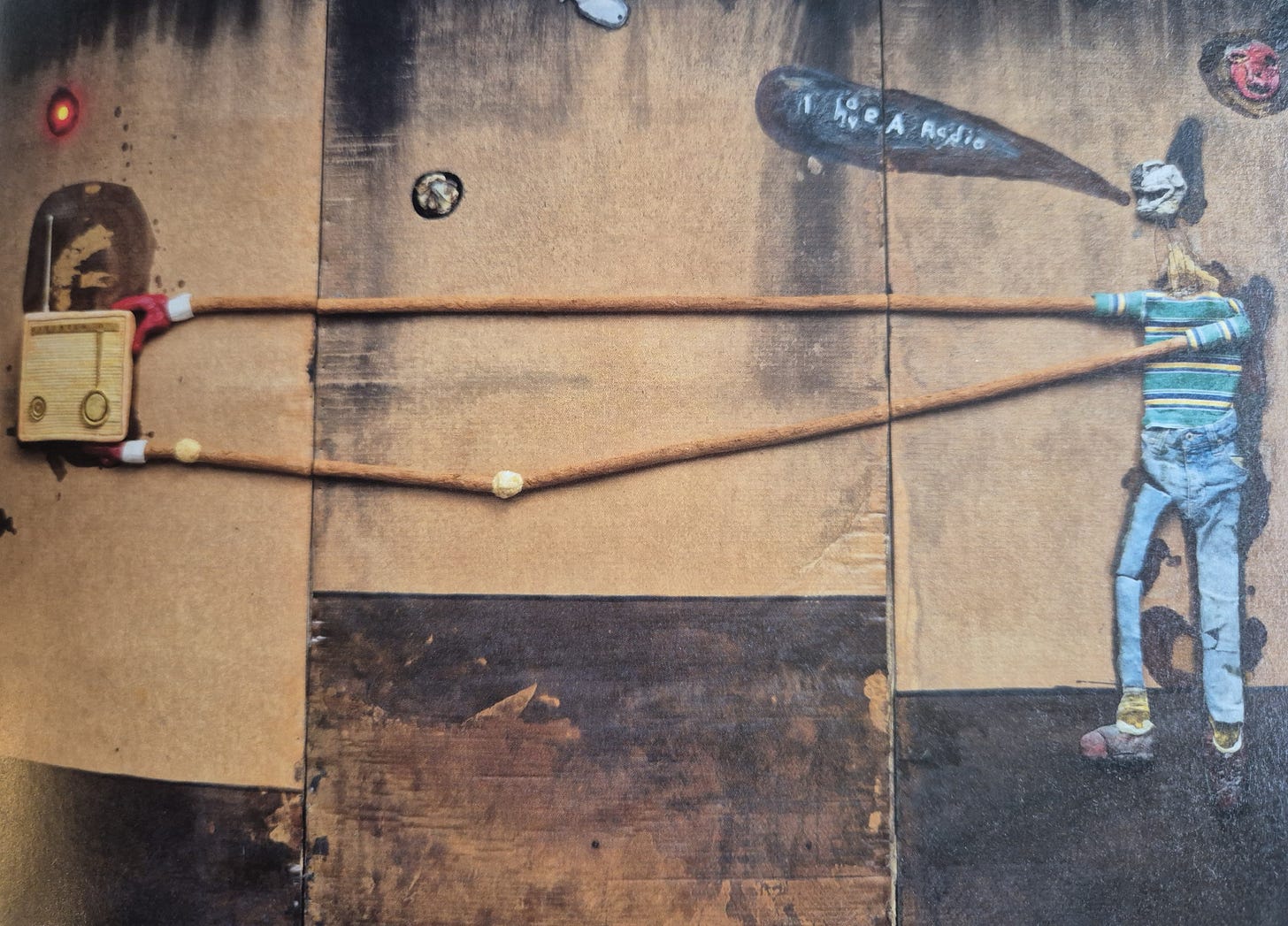

He was also an artist in the (fairly) traditional sense, making paintings, drawings and sculptures. He made music and was frequently credited as a film’s sound designer. As a visual artist, he once explained that he felt his paintings need to “move a little,” hence the transition to filmmaking.

I was watching the film Hereditary (2017) when I learned of his death. I had not seen it before and was remarking upon how ‘Lynchian’ it was, when the news came through that he had died. It is clear to see the impact of his work upon other directors and producers seeking to capture a certain ‘mood,’ an ambience of impending horror or strangeness below the surface of normality. Hereditary was certainly one example of this, with some genuinely frightening moments. And so, Lynch’s death has given cause to revisit my own earlier thesis.

I wrote my dissertation with the idea of questioning the repeated construing of Twin Peaks as merely postmodern fluff in terms of style and approach. There was no doubt in my younger self’s mind that it was indeed a postmodern project. It had many of the hallmarks of postmodernism within the discipline of film studies for sure. It was highly referential, with frequent jokey references to other films such as Double Indemnity (there was a character called Mr. Neff selling life insurance). It was additionally very knowing, sharing jokes with the audience with many red herrings and frequently amusing side notes (the sheriff bore the name Harry S. Truman with barely a flicker of diegetic recognition). However, even then I was questioning the point so frequently made that postmodernism was a depthless utilisation of frivolous style. I felt that Twin Peaks’s humour and jokes only served to enhance and illuminate the seriousness of the main narrative thread, that of sexual abuse and murder.

Twin Peaks, fun and strange though it was, nevertheless explored the hidden abuse that occurs in families and beneath the surface of small towns. Things that appear wholesome and normal are fractured to reveal something rotten beneath the surface – a frequent trope of David Lynch. A further trope was the unreliability and instability of families, and this even extended to those films not written by him. The outward projection of a stage performance - always hiding a backstage world - often presented as a literal theatre can be seen in nearly all of his films. For example, there is some kind of stage with performers in Eraserhead (the lady in the radiator), the Elephant Man, Blue Velvet, Twin Peaks, Wild at Heart and Mulholland Drive.

A theatrical spotlight projected into a domestic living room literally highlighted the resolution to the question raised in Twin Peaks, ‘who killed Laura Palmer.’ The scene demonstrated its own ‘twin’ as Laura’s cousin Maddy was murdered by Leland Palmer, Laura Palmer’s father. This was designed to unconceal the events of the previous murder carried out in the same vein. What still strikes me now as it did then, was the bringing into focus the portrayal of domestic abuse straight into ordinary people’s living rooms. The way Lynch used his abstracted methods served to make audiences see and watch what can go on behind closed doors. As it happens, at the time of the original broadcast, I had not long come out of an abusive relationship. The subsequent familial explosion on screen would normally have revolted me. However, undertaken as it was with Lynch’s surreal twist, I will admit to a catharsis of relief. There was a sense that we were being taken to new televisual territory and the genie was not about to be put back into the bottle.

There were moments of conflict concerning Lynch’s politics. He was often assumed to be somewhat right wing, especially in his portrayals of women. The tight sweaters in Twin Peaks were designed no doubt to show off a 1950s bust in one of the many postmodern jokes. (Twin ‘peaks,’ geddit?) Yes, the females were alluring, beautiful and sexy, but then so were many of the male characters, beginning with MacLachlan as the lead. There were strong females, (Catherine Martell, Audrey Horne) and weak males, (Pete Martell and Andy Brennan). The point seemed to be to find a way to produce twins, doubles, counterparts and doppelgangers.

It was Lynch’s preparedness to pull back the curtain to reveal male violence against women in the moment (and not merely fetishise the dead Laura Palmer) that gave me pause for thought. Lynch had clearly created a fantasy world in Twin Peaks, one which echoed and referenced 1950s American soap operas as well as the detective procedural in a bizarre generic fusion. MacLachlan, as a smartened up Columbo solved crime with Dada-esque bricolage techniques and was not to be taken too seriously. In case people missed the point (and many did) Lynch patiently demonstrated this by showing a deadened reversal of the Double R Diner (based on Lynch’s erstwhile daily sojourns at Bob’s Big Boy) that appeared in the prequel, Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me (1992). Gone were the lovely Shelly and her boss, Norma, no more fabulous cherry pie or ‘damn fine coffee,’ all to be replaced with foul equivalents. Nasty coffee, inedible food and scowling waitresses. This told the audience in no uncertain terms that what they had enjoyed in the world of Twin Peaks was not exactly gone, because it never existed in the first place.

Lynch returned to the unmasking of the pleasurable ideal in Mullholland Drive where two versions of Hollywood collide to expose the wretched darkness bubbling beneath a bright illusory surface. The twin/double idea resurfaces in Lost Highway with two actors playing the same character, who changes from one to the other halfway through.

David Lynch’s knack for rooting into the unconscious with his concept of ‘fishing for ideas’ created worlds as moving canvases to explore both lighter and darker sides of life. In this he was a highly original creative artist. He shocked and delighted his audience by frequently changing direction and taking on projects no one would expect. Without him we would never have had television shows such as The Sopranos, or Dark. Films such as Hereditary, Donnie Darko and I’m Thinking of Ending Things (and may others) owe a great debt to David Lynch’s opening up filmic notions of unstable identities, visionary dreams, unconscious desire, along with atmospheric camera work, creative light and sound design. Hopefully, he’ll be enjoying a damn fine cup of Joe in the best American Diner they can find in the heavens, “where pies go to when they die.” I imagine him digging in to a mighty fine cherry pie and reflecting on a crazy, creative career where ‘the owls were definitely not what they seemed.’

I owe Mr. Lynch a great deal. I certainly owe him my master’s in film. He taught me to think differently about visual art, about painting, film, psychology and human relationships. He taught me to see wonder, beauty and darkness. There are films I’ve watched because of him, art and photography I’ve viewed because of him. He got me to think about meditation, the unconscious, the brain and the mind. He both frightened and delighted me.

I will mourn that he is no longer in the beautiful world. Gone fishing.

Making Inside Outside: Revealing Secrets in Twin Peaks Where the Truth is “In Here,” Rather Than “Out There,” is the title of my MA thesis at the University of Manchester, 1997.

Images as credited. David Lynch’s art work taken from the catalogue, David Lynch: Someone is in My House, London, Prestel, 2018, from the exhibition entitled: My Head is Disconnected, running at Home Manchester, GB, from July-September 2019.

Thank you for reading! Feel free to comment and share.

If you find my writing interesting and worthwhile, I would be glad to receive one-off donations through the Buy me a Coffee scheme. Do subscribe if you haven’t already, subscribing alone supports my work.

Love this article . I remember rushing home from wherever I was , to watch the latest episode of Twin Peaks. It was weird and wacky , funny and disturbing all at the same time. The Bob character really terrified me ! I’me not familiar with David Lynch work generally, but this article has made me want to check it out 👍

Lovely overview of his oeuvre. Thank you.

I love Lynch's films but have never watched Twin Peaks apart from a couple of episodes. Now on my watch list.