An Eye for an Eye Brings Clarity and Justice

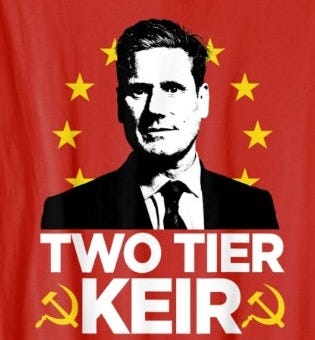

Elon Musk derides the biblical exhortation; Peterson doesn’t interrupt to correct. Surely it is the logs in eyes that blind people. What about endorsing an ‘eye for an eye’ for Two Tier Keir?

To see is to understand. To have vision is to progress.

Does Elon Musk believe that the rich should have an advantage over others? It might be a slightly unfair question to put to the richest man in the world. With his casual disparagement of the biblical ‘eye for an eye’ rule in the recent interview on X with Dr Jordan Peterson, Musk missed an opportunity to ram home the point about fairness. This is because the ‘eye for an eye’ rule insists on equal treatment for rich and poor alike.

In that interview, Musk related to Peterson that at the age of twelve, he had read a plethora of religious texts by all the great thinkers. Twelve is a most interesting age for that given the many legendary biblical twelve-year-olds.[1] Not least of which is the renowned twelve-year-old Jesus, found in the Temple arguing about the Torah in true Jewish fashion with the elders (Luke 2: 41).

One guesses that Musk’s swift dismissal relates to the supposed savagery of the ‘eye for an eye’ judgement which is frequently inferred. Few seem to support it. Is it not all about revenge? Christian commentators shy away from its more nuanced meaning preferring to focus on Jesus’s words which are assumed to contradict the ‘eye for an eye’ statute. Most find the casual acceptance of passé definitions rather too easy. This approach reveals much about a generalised desire to situate Judaism as a primitive anachronism to be overcome instead of an important, nay crucial ally in the current prevailing winds. Moreover, it is interesting to note Musk’s disavowal of his long-rumoured Jewishness alongside his claim to be an Anglican in conversation with Dr Peterson. Arguably a Protestant work ethic suits the busy Musk.

Whatever Musk’s own religious affiliation, he cited the phrase ‘eye for an eye’ as if it were something destructive, brutal and primitive. Was he reaching for the words of Ghandi, one known to have made the (erroneous) claim that an eye for an eye would render the whole world blind? That was clearly the sentiment we were supposed to understand by Musk’s words. However, on this Musk, like Ghandi was wrong.[2] As with many aspects of the Bible, that collection of books few bother with these days,

it’s complicated.

An ‘eye for an eye’ appears three times in the Old Testament Hebrew Bible. Exodus 21: 23-25, Leviticus 24: 19-20 and Deuteronomy 19: 21. Additionally it is cited in the New Testament by Jesus as he teaches the scriptures, (a point to which I shall return). In Exodus, we read about punishments outlined for having caused physical harm to someone.

“…life for life,

eye for eye,

tooth for tooth,

hand for hand,

foot for foot,

burn for burn,

wound for wound,

stripe for stripe.”

The ‘eye for an eye’ rule is not an exhortation to blind someone or chop off his limbs. The point of this statute is that the punishment should be proportionate and fit the crime. A.J. Levine writes that the measure for measure concept is cross cultural. The Roman ‘law of equals,’ the Lex Talionis (451-50 BCE) permitted the victim of violence to inflict the same injury upon a perpetrator. Additionally, the Babylonian Code of Hammurabi contained similar injunctions.[3]

The ancients realised that any attempt to render the statute in a literal way would not work, even on its own terms. What if the guilty party were already missing an eye? To blind him in the remaining one would result in an excessive punishment which would then no longer constitute an ‘eye for an eye,’ or a measure for measure. Realising that such literalism could never achieve the required fair outcome, a system of monetary compensation was established.[4]

Therefore, rather than a savage bloodbath, the biblical ‘eye for an eye’ rule seeks to exact a fair outcome when damage or hurt has been inflicted. The idea is that the wronged person shall, as far as possible, be restored to the previous state before the error occurred. If a loss is suffered, then the loss shall be made good. In this way, I interpret this as a prototype of restorative justice as it seeks to restore, not avenge. Additionally, and importantly, the rule is likely to have been designed to prevent excessive vengeance, as in no more than one eye, one life, and so on thereby stymying the potential spiralling of violence. Above all, it is about fairness. Furthermore, as Douglas Knight and A.J. Levine explain, the lack of any subsequent mention of the majority of biblical laws we read about in biblical narratives would suggest that they were not enforced in reality. They should be understood as akin to stated ideals rather than hardline rules.[5]

Moreover, as Elon Musk might take note, biblical law insists that ‘the rich’ should not have advantages over the poor when it comes to judgements and punishment. This is because the ‘eye for an eye,’ measure for measure applies equally to all, whatever his status. Therefore, a rich person’s eye is not worth any more than a poor person’s. As Dennis Prager points out, the contemporaneous Babylonian Hammurabi legislated that the eye of a nobleman was worth more than a common person. It therefore imposed variable fines depending on the status of the injured victim. There is a further point demonstrating the matter of fairness. In the same Babylonian code, if for example someone were to kill a man’s daughter, then the wrong doer’s daughter would be executed as punishment. Whereas the Hebrew Bible’s ‘eye for an eye’ rule insists that only the guilty party should be punished, and no one should be punished on behalf of someone else. The ‘eye for an eye’ rule should be understood within this historical context, and not by the assumptions derived from ignorance or religious prejudice. As for Elon Musk, I bet that this emphasis on fairness and the de-escalation of conflict would meet with his approval.[6]

Notwithstanding the frequent assumptions, the measure for measure, ‘eye for an eye’ principle is one that informs the modern world. By way of an example, if an employee were to sue an employer in Britain, the compensation payable for losing an eye ranges from £44,000 to £55,000. We literally have a rule on the books today that is an ‘eye for an eye.’

Where the Bible does take the measure for measure rule literally is in the case of murder. As Dennis Prager writes in his Rational Bible series, in Genesis, capital punishment is understood to be part of the moral foundation of civilisation.[7] Today, many would posit capital punishment as the quintessential act of cruel revenge. Modern awareness of the state’s power of ultimate force over its citizens and the ever-present potential for state overreach raises serious questions about the morality and ethics of capital punishment. And the ancient rabbis probably thought along those lines as well. This is why they sought to find ways to mitigate the death penalty and to distinguish between what we refer to today as manslaughter and premeditated murder.

It is worth noting that the Torah repeatedly insists that the stranger, foreigner or visitor should have the same legal rights as an Israelite.[8] So, the outsider, the non-Israelite is protected in this ancient Hebrew system. Furthermore, the stranger is not obliged to worship alongside the Israelite, meaning there is no requirement to earn these rights. They are given freely, and without obligation. This is what has come down to us from biblical precepts. Where the screechy young ‘wokist’ assumes that the Bible is nothing more than a manual for slavery and oppression without ever having properly engaged with it, the very rights she depends upon have more than likely been derived from that very set of texts. To be more precise, the Bible forms the foundation of western civilisation. I would argue that only in such a civilisation can women’s rights (as we understand them) truly be upheld.

Throughout his ministry, Jesus frequently refers to the Hebrew Scriptures, citing them, alluding to them and teaching them.

In Matthew, he endorses the Torah in clear and unambiguous terms. He says,

“Do not think that I have come to abolish the Law or the prophets; I have come not to abolish but to fulfill, amen I tell you, until heaven and earth pass away, not one letter, not one stroke of a letter will pass from the law until all is accomplished.” (Matt 5:17-18)[9]

As Charles Talbert explains, Jesus’s intent is to realise the intent of God’s will in the scriptures.[10] So, rather than negating the Torah, as is frequently assumed, Jesus does what is known as ‘building a fence around the Teaching.’ This is when he extends some of its precepts, enlarging upon them to ensure that disciples and followers remain within the guidelines and so lessen the risk to sin. This means that we could say that Jesus makes an extra effort to keep the Torah, the Teaching, the Instruction (the Law) safe, upheld and guarded. Misunderstanding this leads to a serious misreading of Jesus’s words in Matthew (5-8). They are not ‘antitheses’ at all, they are extensions.[11]

I now want to move towards what Jesus does with the ‘eye for an eye’ injunction which he addresses as part of the sermon on the mount.[12] Jesus adopts a pattern, which declares, you have heard it said and then citing a statute and then extending it by saying but I say to you...[13]

For example, in Jesus’s teaching on adultery, Jesus shows us that it is the desire for someone that can lead to taking that first step towards adultery. He says,

“You have heard it said that you shall not commit adultery, but I say to you that everyone who looks at a woman with lust has already committed adultery with her in his heart.”[14]

When Jesus refers to someone desiring a woman, his point is that the ‘someone’ has taken a step towards committing adultery. Therefore, by doing this, Jesus is getting us to think about that first step. This is the one that should be curtailed. We can deduct from this that adultery for Jesus is something that begins within the mind before being enacted by the body.

Additionally, it might be worth noting that contrary to what most assume (especially from film portrayals) Jesus is not actually teaching the crowds here. Rather he has taken his closest disciples to one side, and he is teaching them, in order that they can go on to teach others. Furthermore, Jesus teaches his disciples and the people from his own authority. He does not cite other great teachers such as Hillel or Shammai or even John the Baptist. He says, “I say to you.” This is significant. Additionally, to underpin this authority, we should take note of the idea of a sermon on the mount. How often do biblical figures ascend a mountain to encounter the divine? This would have been completely comprehensible to Jesus’s audience as first century Jews. This also signifies Jesus’s authority in its authentic sense, as author-ity. He is the author of this teaching.

And so, we come to an ‘eye for an eye,’ (Matt. 5: 38).

Jesus said:

You have heard it said an eye for an eye, but I say to you…do not resist an evildoer. And if someone strikes you on the right cheek, offer him the left.

In more modern phrasing we could understand it thus, “You have been taught (about)… an ‘eye for and eye,’ and I say to you, I am going to give you my teaching my layering and my fence around that Teaching, that Way, that Law.”

Given that what Jesus does frequently is not to condemn the original, but to enlarge upon it we are now presented with an interesting puzzle. What is he trying to say here? And given also that the ‘eye for an eye’ statute asserts the requirement for fair compensation for loss, and “equalises all bodies and limits vengeance,” it is in actuality, a statute that is hard to extend in the way that Jesus does for other statutes. Therefore, what Jesus does is to make a sideways move. As Levine explains, “he changes the subject.”[15] In doing this, Jesus leaves the statute intact. He does not change it. When he speaks of a slap, his disciples would have understood this as the slap of dismissal and humiliation. And so, Jesus extends the ‘eye for an eye’ statute by moving it out of the realm of actual physical violence and into the very kind of thing his followers were likely to experience as they came up against resistance to Jesus’s teaching. As Levine explains, Jesus does not dismiss an ‘eye for an eye,’ rather he uses the statute to teach about dealing with public humiliation in keeping with the de-escalation required of the law (i.e., an ‘eye for an eye.’). She points to references such as Lamentations where it says about “giving one’s cheek to the smiter and be filled with insults” (3:30) and in 2 Corinthians (11:20) where Paul speaks of being slapped in the face. The thinking is that you will not escalate the situation into violence if you offer the other cheek which would be clumsier to slap. Yet, shrinking back risks losing face. How to deal with humiliation without losing face is the lesson here.

Jesus continues,

“…and if anyone wants to sue you and take your coat, give your cloak as well; and if anyone forces you to go one mile, go also the second mile.” (5:39-41)

The example of the coat refers to the practice of being sued. Once again, Jesus makes use of scripture. Exodus 22:26-27 speaks of the pawning of a coat that may be someone’s only possession. By offering up one’s cloak in addition to the coat when being sued, one has the opportunity to lay bare (literally) the injustice at hand.

Furthermore, by going the extra mile, one asserts agency when being compelled under the threat of force. Compliance would mean humiliation. However, taking on the extra mile is to confound the bully and show up injustice.

Therefore, we can see Jesus’s references to the slap, the lawsuit and the subjugation as an endorsement of the ‘eye for an eye’s’ propensity to de-escalate a situation. In this way, we can see how subtly Jesus has actually extended the ‘eye for an eye’ statute. Levine interprets Jesus’s words:

“do not escalate violence, do not give up your agency, shame your attacker and retain your honor (sic).”[16]

I would argue that Jesus, far from trying to correct the statute of an ‘eye of an eye,’ he both honours and provides a ringing endorsement of it. Moreover, Jesus advocates an intellectual, mindful response when teaching his disciples how to deal with humiliation. Nowhere does Jesus suggest that you forego your entitlement to compensation. What he appears to be saying is do not react in a way that might be expected. Confound your attackers’ expectations.

Additionally, turning the other cheek is not a disavowal of the compensatory aspect, it is the taking on of unfairness yourself. As The Oxford Bible Commentary explains the examples proffered on the mount mirror the events of Jesus’s own arrest and crucifixion to come.[17]

Jesus’s propensity for interpretation is entirely in keeping with Jewish tradition. Debating and discussing, with the differences in outlook are part and parcel of biblical engagement in both testaments. The Gospels themselves do not align fully, and the Hebrew Bible is very much a compendium of ideas, some contradictory. Every episode has its context, backstory and links. Many modern-day religious biblical scholars understand the diversity of thought that is present in the Bible, and that this is important.[18] As Amy Jill Levine points out, the right to interpret the laws governing us is an important aspect of both biblical and modern life.[19]

To condemn Jewish thinking as if it were all summed up in the phrase ‘eye for an eye,’ when assumed to be concerned only with aggressive vengeance is to do everyone a disservice. Not least Jesus himself. Especially as this teaching is in actuality, rooted in concepts of fairness and justice. We can take our exploration further. Jesus goes on to use the phrase measure for measure in a most interesting manner. In Matthew 7:2, He says:

“For with the judgement you make, you will be judged and the measure you give will be the measure you get.”[20]

He then asks:

“Why do you see the speck in your neighbour’s eye, but do not notice the log in your own eye?”

Jesus’s use of the phrase measure for measure supports the argument that he endorses the underlying principle behind an ‘eye for an eye.’ Cleverly, Jesus returns to the image of an eye in his examples. In the biblical world, as in our own, to see is to understand. To have vision is to have the imagination to progress. What Jesus offers is a sophisticated and highly intelligent midrash upon this principle. In this way he is teaching others how to interpret it. And so, through ancient texts that have preserved us and brought us to this moment, Jesus is giving us his in-sight upon how to interpret an ‘eye for an eye.’

Given the draconian punishments meted out in Britain over the past few weeks the importance of justice, fairness and proportionality seems more urgent than ever. People have been sent to prison without trial, labelled as criminals without evidence, incarcerated for up-ticking or sharing social media posts. Who wears the logs and who carries the splinters here?

Interestingly, into this mix, Elon Musk’s interventions have confounded the expectations of the new Labour prime minister who has acted with a striking display of raw authoritarianism. The very essence of ‘Two Tier Kier’ is the cynical disavowal of an ‘eye for an eye’ that stands in stark contrast to Jesus’s teaching.

Quite simply we have seen disproportionate punishments for wrongdoing that are way in excess of the supposed crime. We are also seeing a perverse inversion of justice in the number of violent offenders who will be released from custody to make room for these first-time keyboard offenders. More than ever, we need to see the principle of proportionate punishment and the de-escalation of aggression. Starmer had the opportunity to be statesmanlike, calm and to show wisdom. He might have acknowledged the pain and the suffering that gave rise to some of the expressions of frustration and aggression. He might even have placed some emphasis upon the murders of three innocent little girls who seem to have been forgotten in all of this noise. Instead, he marshalled his new powers in the most ominous and strident manner, and he did so with relish and without mercy.

Musk has pointed out on X that fairness needs to be applied to all communities if there is to be fairness at all. This point is, ironically, the very essence of an ‘eye for an eye.’ Jesus might additionally challenge our rulers to consider the great logs that are jammed into their eyes whilst they fret and disparage the splinters of protestors, some with no hope of employment or housing because the colour of their skin and their allegiance to their national identity is deemed to be beyond the pale.

You have heard it said that Jesus is criticising the eye for an eye rule. But I say to you that he is protecting it, enlarging it and bringing wider intelligence to bear for its sake.

Elon Musk, Jewish or Protestant (who cares?) what about endorsing that ‘eye for an eye’ for Two Tier Keir? Surely it is the logs in the eyes that blind people. As Musk might now affirm, an ‘eye for an eye’ brings clarity, fairness and justice.

Thank you for reading! Feel free to comment and share.

I do not charge for subscriptions, however if you find my writing interesting and worthwhile, I would be glad to receive one-off donations through the Buy me a Coffee scheme. Do subscribe if you haven’t already, subscribing alone supports my work.

[1] Legendary biblical 12-year-olds include Samuel, Solomon, Josiah and Daniel according to Roger David Aus, Samuel Saul and Jesus: Three Early Palestinian Jewish Christian Gospel Haggadoth, University of South Florida, 1994, 24.

[2] I would concede that both Musk and Ghandi may be mistaken rather than “wrong.” However, the frequency with which this particular biblical phrase is trotted out in an attempt to illustrate some imagined brutality of Torah, or the Old Testament and by extension the Jewish people, it necessitates an unequivocal refutation.

[3] Amy Jill Levine, Sermon on the Mount: A Beginner’s Guide to the Kingdom of Heaven, Abingdon Press, Nashville, 2020, 37-8.

[4] Mishna Bava Kamma 8:1; Babylonian Talmud Bava Kamma 83b-84a cited in The Meaning of the Bible: What the Jewish Scriptures and the Christian Old Testament Can Teach Us, Douglas A. Knight and Amy Jill Levine, Harper Collins, New York, 2011, 124.

[5] Knight and Levine, The Meaning of the Bible, 125.

[6] Dennis Prager, The Rational Bible, Exodus: God, Slavery and Freedom, Regnery Faith, 2018, 301.

[7] Dennis Prager, The Rational Bible, 2018, 301.

[8] Examples include Leviticus 24:22, Numbers 15:15-16, Exodus 12:49, Deuteronomy 24:17.

[9] There are a number of arguments around the meaning of the word fulfill in this context. See Levine, Sermon on the Mount, 2020, chapter 2, 23-24, Charles H. Talbert, Reading the Sermon on the Mount: Character Formation and Decision Making in Matthew 5-7, University of South Carolina, 2004, 59-60.

[10] Talbert, Reading the Sermon on the Mount, 59.

[11] See Levine, Sermon on the Mount, 2020, chapter 2, 23-43.

[12] Which is arguably not really a sermon at all, rather it forms a list of discrete teachings as A.J. Levine explains in her introduction to Sermon on the Mount, 2020, ix-xi.

[13] The translation ‘and’ is more accurate than ‘but’ here.

[14] Matthew 5:27-28 where Jesus cite Exodus 20:14, Deuteronomy 5:18 and Leviticus 20:10.

[15] Levine, Sermon on the Mount, 2020, 38-39.

[16] Levine, Sermon on the Mount, 2020, 39-40.

[17] John Barton and John Muddiman, The Oxford Bible Commentary, Oxford, OUP, 2001.

[18] See Peter Enns, How the Bible Actually Works, Hodder and Stoughton, London, 2020 and Yoram Hazony, The Philosophy of Hebrew Scripture, Oxford, OUP, 2012.

[19] Amy Jill Levine, The Misunderstood Jew: The Church and the Scandal of the Jewish Jesus, Harper One, New York, 2006, 202-3.

[20] Matthew 7:2. Jesus also uses the phrase ‘measure for measure’ in Mark 4:24, and Luke 6:27.

Excellent exposition (sic) of the highly-significant contrasts between foundational elements of, respectively, the Hebraic worldview, rooted in the Torah, the Messiah's teaching of the Way and the multi -tiered Babylonian system, so eagerly embodied by confessed "atheist", Starmer, whose actions ruffly betray him and his allegiances.

Enjoyed this essay... it is well-known how difficult it is to allow for the passage of time in understanding culture and ethics, and yet we seem to be getting far worse at doing this too. George Santayana warned of the dangers of not learning the lessons of history, to which Sting added his blunt assent: "History will teach us nothing." How sad it is to admit that.

Stay wonderful!

Chris.